by Brian Long

The Latin for hearth is ‘focus’ and since the earliest times the fire in the hearth has been the central focus in most homes. The continuous emission of smoke from a house used to indicate the wealth or social standing of a householder and ‘fomage’ was a tax on hearths, at one time known as Peters Pence as it was originally to produce revenue for the Pope.

Importantly from our point of view as miniaturists it was instrumental in restricting the number of fireplaces in most homes to one, with specially designed and separate kitchens being in many instances a late innovation. If you had one of the better houses and you had a parlour or withdrawing room, it would be without a fireplace, being a rather drab but private area.

A centrally positioned fire was the natural heart of a house providing light, heat and a means of cooking, at least in winter, with many people cooking outside in summer. A central fire where the Master of the house, his family and his servants would ‘gather round’ on a winters night to gossip, moan about life, sing traditional songs and doze. A place where you could toast your oatcakes no matter where you sat in the circle.

Examples of central hearths come from houses of all periods and all levels of society with a Tudor one at Penshurst Place and, drawn here, a 1930s one from the Highlands of Scotland. From our point of view it makes all the walls available for the display of furniture as there was no chimney breast.

All fires, no matter what the fuel used, require special tools, baskets or ranges to ensure they function properly so a wealth of tradition has built up round its warming embers.

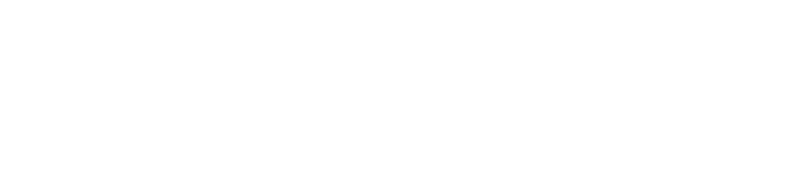

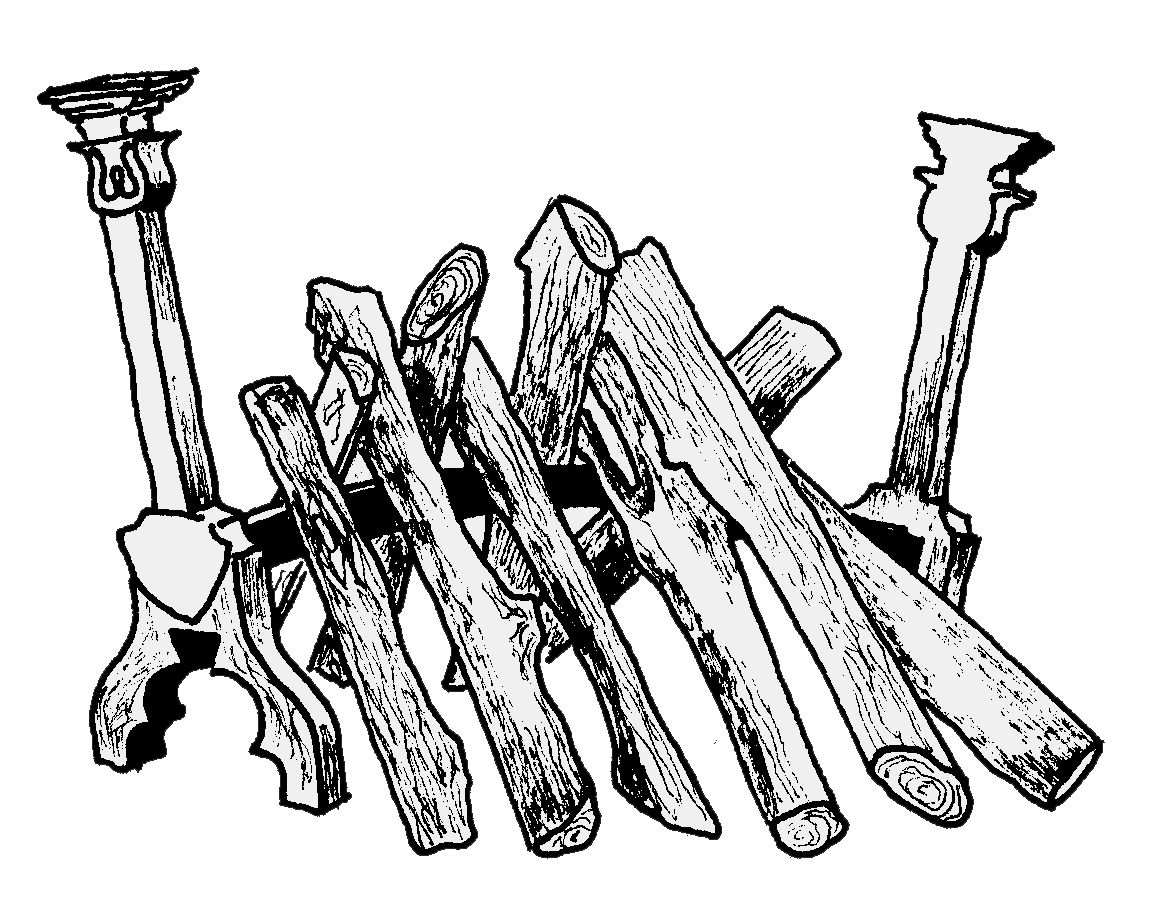

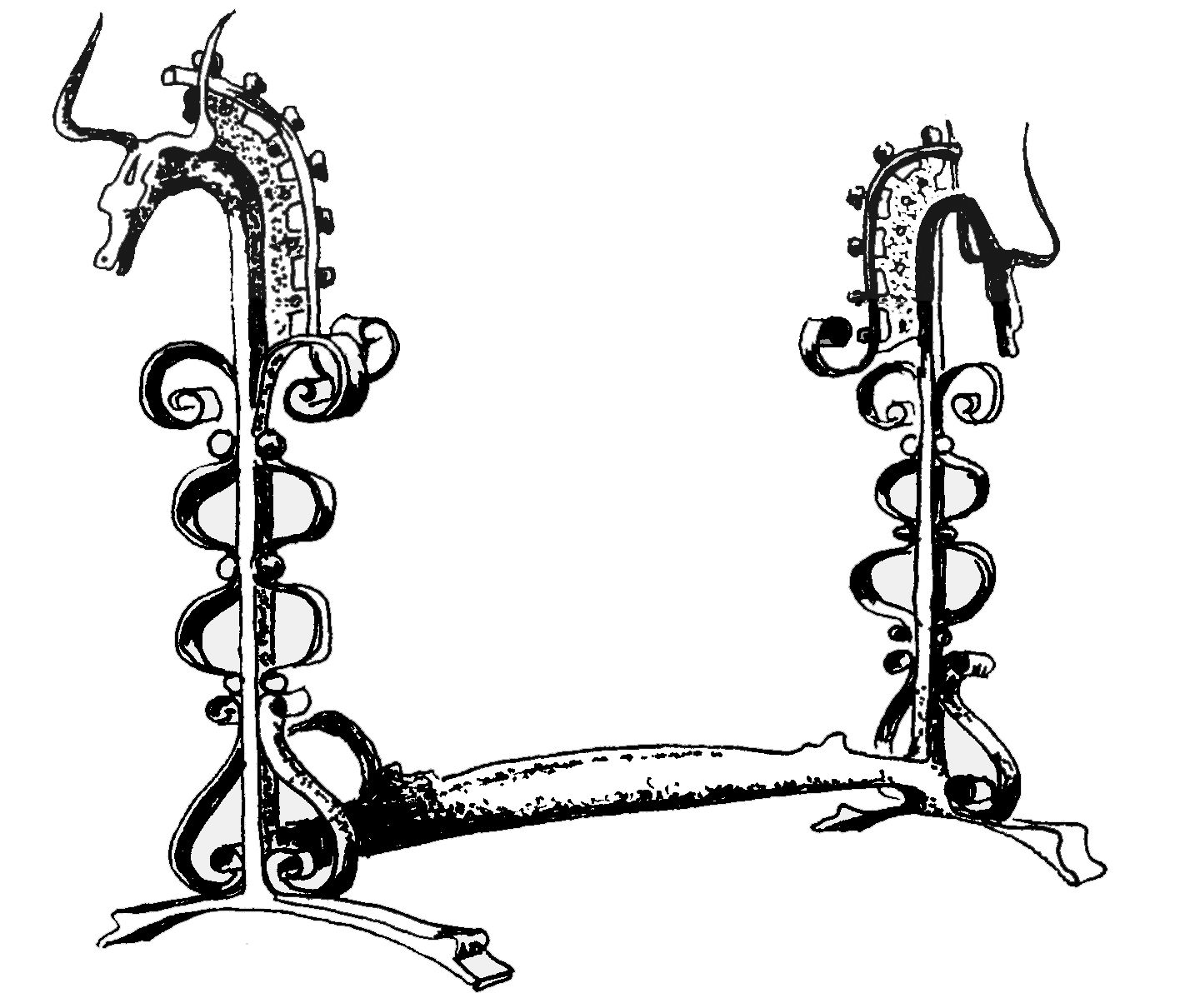

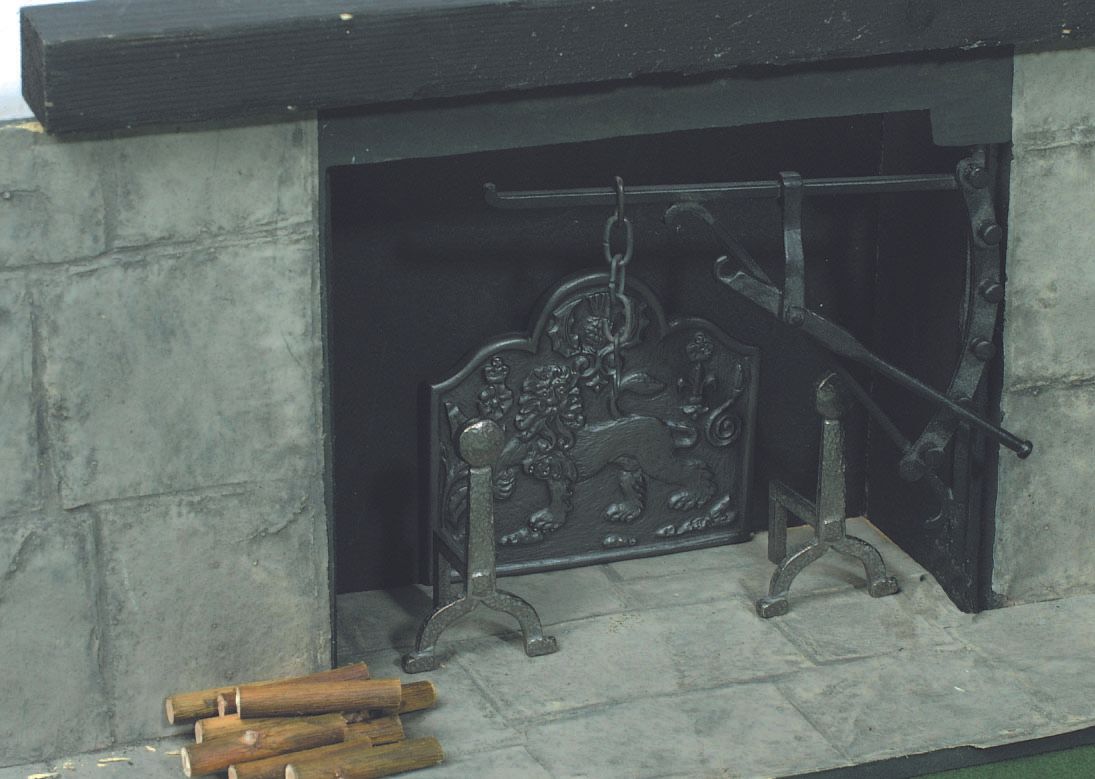

Log fires, centrally positioned, require fire-dogs of a double ended type with examples going back to the early iron age in North Wales and much later Tudor ones at Penshurst Place, Kent. These not only prevented burning logs rolling all over the hall floor but held them up allowing a draught to flow under them to encourage their burning.

Even in the Georgian period free-standing fires in the form of portable charcoal burners were still being used in the halls of our universities. Others were used to heat carriages and unheated rooms in houses of quality even under the dining table to warm cold feet and legs.

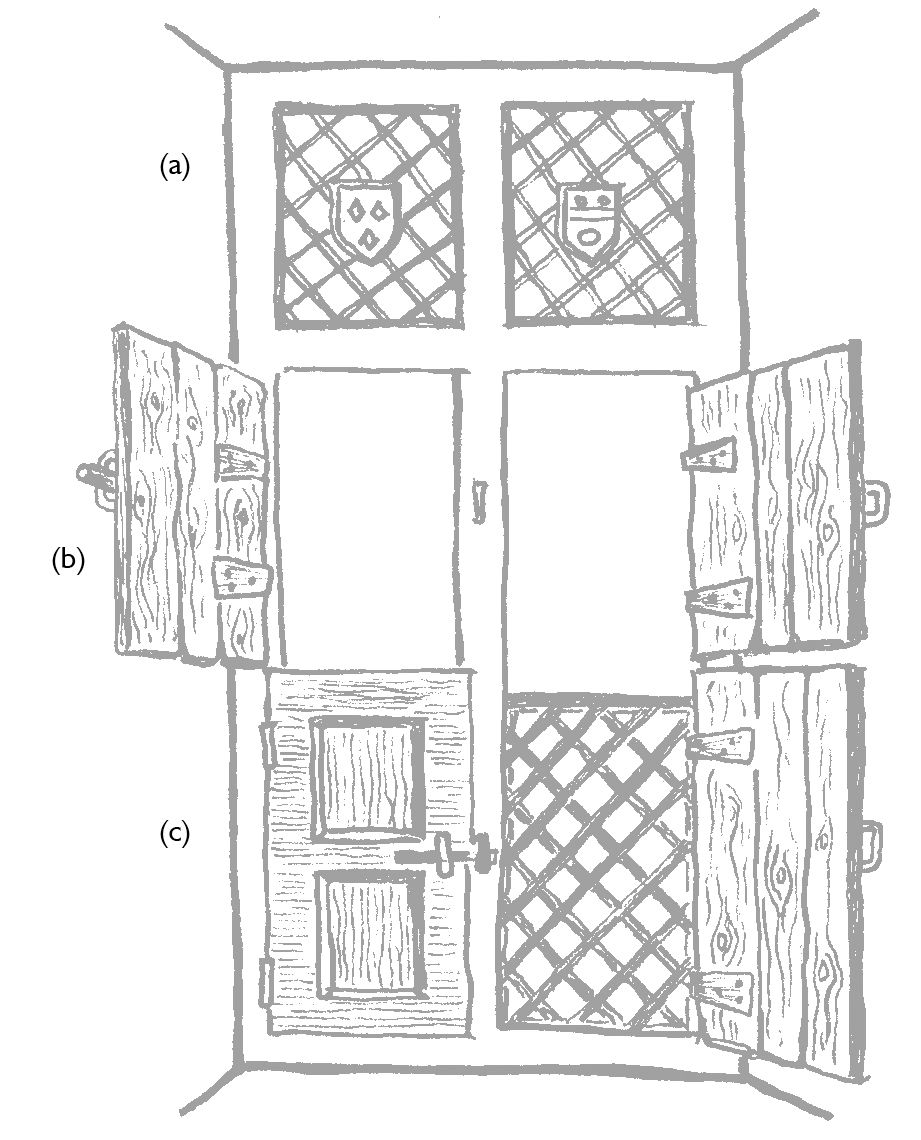

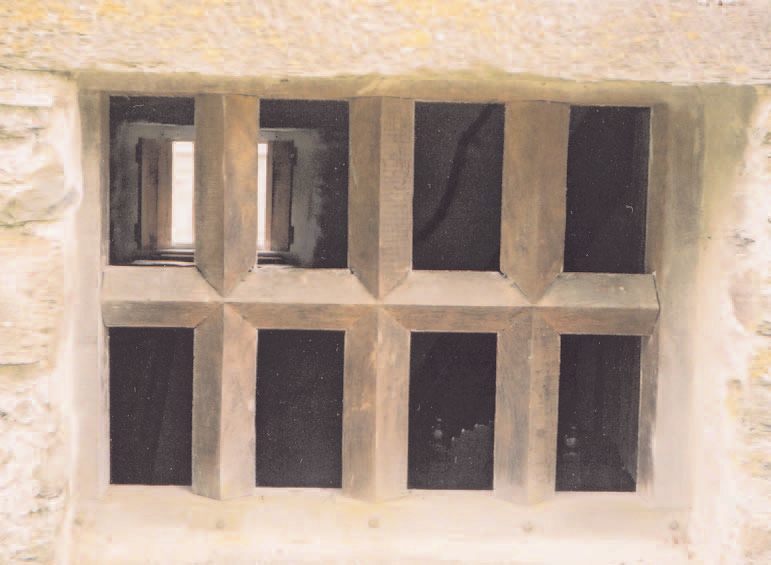

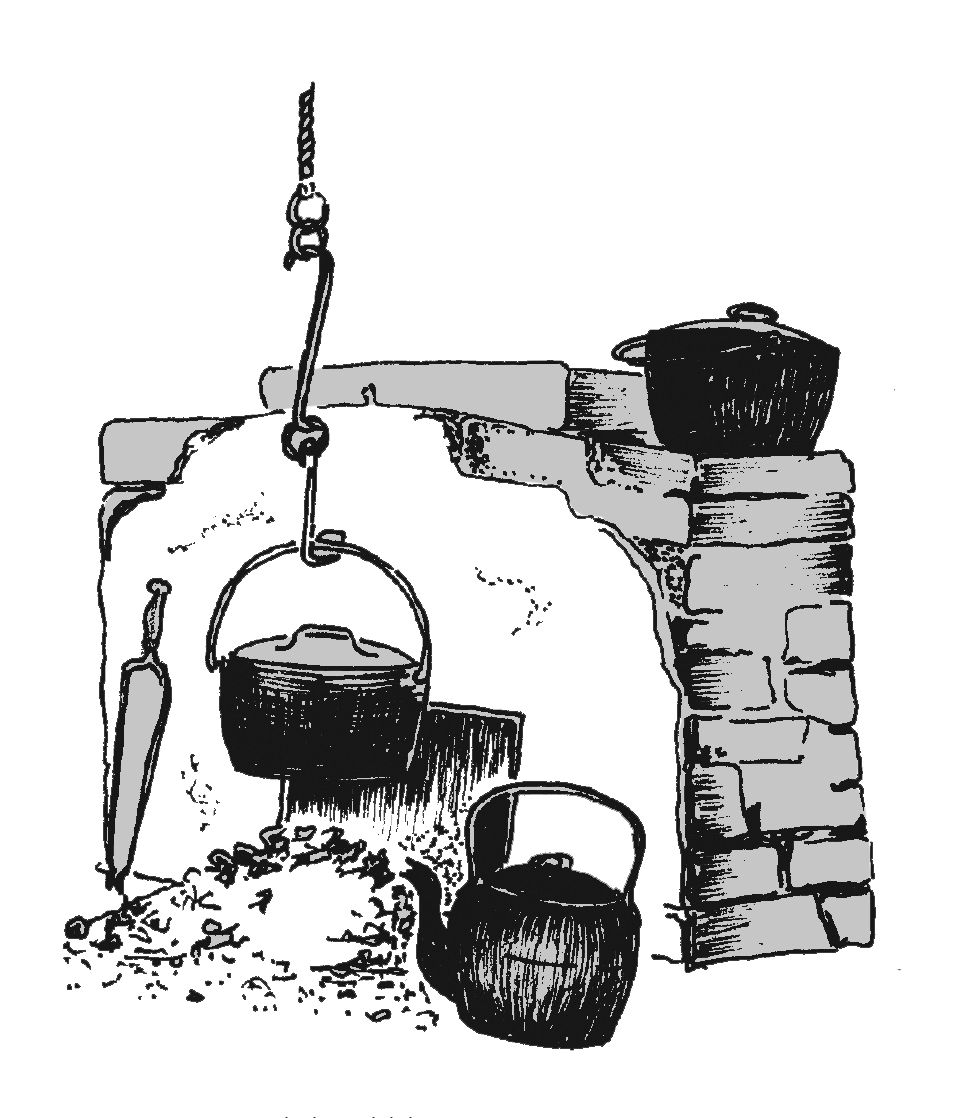

To cook over a central fire required a tripod or series of adjustable chains and hooks hanging from a beam to suspend cooking (c) pots over the heat. All offending fumes escaped via chinks in the roof and unglazed windows, it taking a while before good glazed windows obliged the use of a louver on the ridge of the house.

The next step was more to aid cooking - the introduction of a low wall or re redos as the back of the centrally placed fire. Later still the re redos was positioned against an internal wall and given time a hood was introduced to encourage the fumes to the louver.

With a few tweaks the fireplace as we know it had arrived.

Your doll's house could be of any date and still have these simple fires and flues as it is within living memory (not mine) that open central hearths were used in parts of Scotland, Ireland and upland England and Wales.

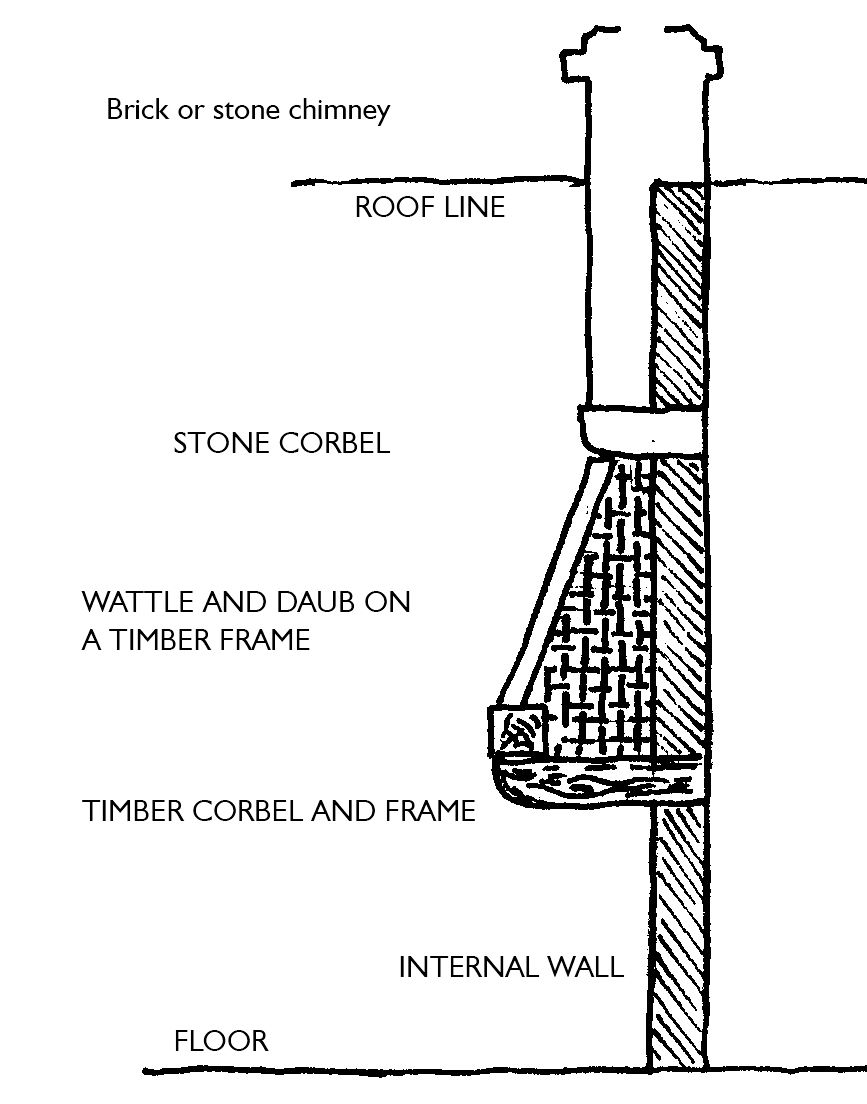

The wattle smoke hood or canopy was known as the brace or breast and rested on a stout brace beam, wood or stone. It was with the adoption of the chimney in one of its many forms that internal partitions within a house were carried up to the roof and an upper floor inserted contributing greatly to the comfort and privacy of the household.

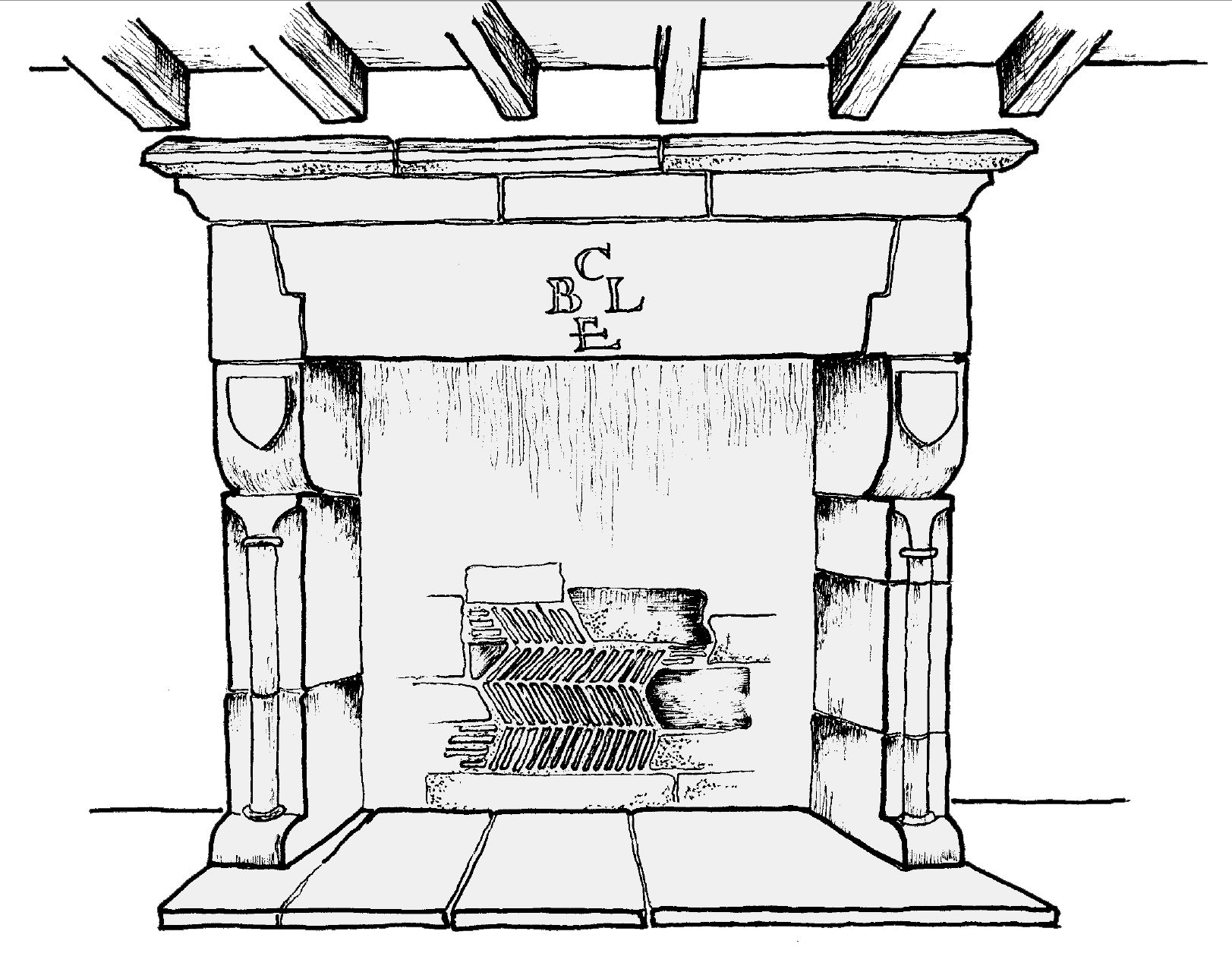

With fires positioned against a wall recesses were incorporated to hold salt or spices and since c500 BC at Skara-Brae it has been traditional that women occupied the left-hand side of the fire, using the cupboard on that side, and men the right. So in these important little wall cupboards, or ‘Boles’ as I remember them, clay pipes and tobacco boxes were put in the right-hand one and sewing or knitting etc., in the left. It is these little things that really make a doll's house.

A further development was just showing off, and even gives doll's houses a boost, and giving status to a house in Tudor England. The chimney was made more visible by building it against an outside wall only to come back inside in the mid-Georgian era giving us the recesses either side of the chimney breast so beloved by miniaturists.

As most food was burned or boiled over ferocious fires, chimney cranes were used to support large pots and pans. These cranes were for the most part simple with some even being made of wood but many were works of art by the best in the Blacksmith’s world.

Ovens were not all the ‘hole in the wall’ type but could be anything from a stone slab projecting from the back wall of the fireplace under which a fire would be lit and simple scones baked on the hot surface. Known as a bake stone this was the forerunner of the grid-iron and trivet on later ranges. In other homes an upturned cast iron pot was placed over the bread then pushed into the side of the fire hot embers were piled round it. There was a special pot with a flat bottom and a depressed lid which hung over the fire with embers placed in the depression of the lid.

A more sophisticated variation was the ‘Terra Cotta Clay’ cloam oven manufactured in Devon until the 1930s and marketed worldwide. These could be built-in as in the Old Post Office, Tintagel or used in the same way as the upturned cauldron above. Timber was used to build ships, houses, carriages, furniture, to heat furnaces and cook food, so in various parts of the country by the mid 16c it was in short supply. In the cities at least coal was being burnt and its use was encouraged by the Great Plague of 1665 when the medics of the time suggested that fumes were beneficial in the fight against distemper.

The first coal burning kitchen grate was introduced in 1760 and towards the end of the century many experiments incorporated an oven and boiler. But most were a disaster and the 1760 hob grate was produced well into the 19c.

Wood as a fuel was now a thing of the past and the more efficient cast iron range was upon us.

BELOW: Firedogs of the central hearth of Penshurst Place in Kent, showing how logs would have been supported.