At the heart of every kitchen is the sink, but why show it all sterile and clean when you can dish the dirt?

If you get stuck over the kitchen sink, spare a thought for 18th century folk. Their sinks were very basic and made of stone or lead sheeting, although shallow earthenware sinks were used in homes around pottery towns. The Victorians paid more interest in their sinks, developing the Belfast, the butler’s sink and the gamekeeper’s sink, so called because it was roomy enough for the gamekeeper to clean off his game.

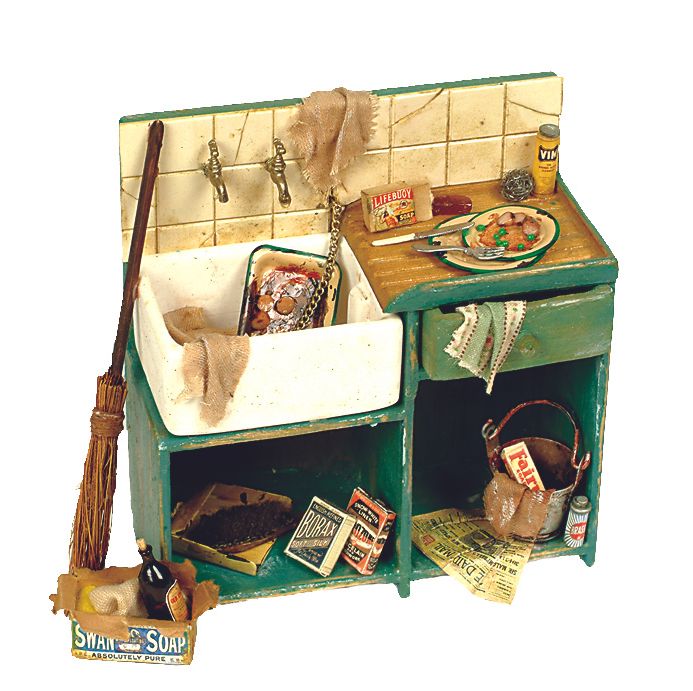

All these weighty sinks required solid support and would be held up by brick sides or built in to a strong cupboard or unit with a cutaway front.

The advantage of these sinks is that they were deep enough to take the large pots and pans produced by busy kitchens, although, as we see here, the tendency can be to pile in the dirty dishes and not have room to move. What a great way to feature a sink in a doll's house–instead of a clean, white square that appears sterile in imagination, pile in those dirty dishes and leave a tea towel hung up, maybe some rubber gloves hanging over the side and some unsavoury looking equipment and detergents on the drainer at the side.

Even the most well-kept Georgian household produced a fair amount of dirty dishes, so while the rest of the house may look tidy and pristine, go ahead and show the kitchen as the workplace it was meant to be. After all, you don’t have to do the washing up!